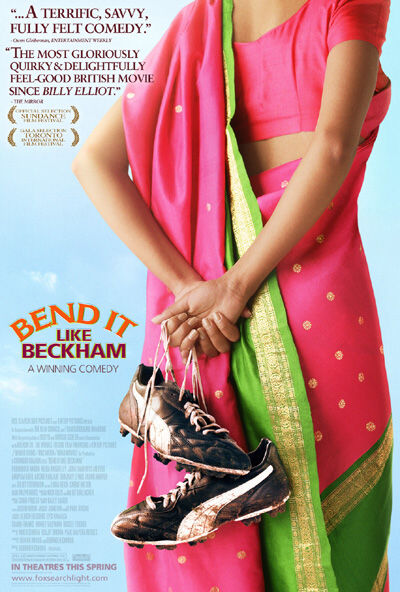

Bend it like Beckham

by Daniel McNeil

M. A. History, University of Toronto

April/May 2003

Bend it like Beckham celebrates the struggle of Jess, a south Asian teenager, to play football (soccer) against her parents’ wishes. Like the famous Manchester United player, Jess seeks to create magic on the football field, and has had her exploits projected in front of thousands of spectators. Bend it like Beckham is the most profitable all-British film of all time and has recently been released in Canada and the United States. It demands critical reflection from “multiracial/cultural” individuals and “visible minorities” in the UK and North America, if they wish to know how their “role in the national team” is being imagined in the twenty first century.

Chadha, writer and director of the film “made a conscious decision to always operate in the mainstream, but to make films about people you don’t normally see in the mainstream. Beckham deals with gender, deals with sexuality, deals with cultural identity, deals with Britishness and all those things, but it’s totally dressed up as a teen movie.”1 Despite her disparaging comments about the American film industry,2 in Bend it like Beckham, Chadha still offers America (or at least California) as the land of opportunity/money (eying the Hollywood market and soccer moms, along with her American husband and home in California) and seeks a generic, middle class, suburban solution to society’s ills, albeit one that is not as segregated as the US.

Bend it like Beckham works on the basis that suburban people can “identify” with the movie. Like My Big Fat Greek Wedding, such middlebrow attempts to show middle class consumers themselves often refuse to engage seriously with economic privilege, racism or sexism. Instead they tend to fit themselves into a multicultural mosaic and develop “undemanding, unambitious comedy,” where the future of the West is saved from old-fashioned (world?) prejudice and discrimination, and tied to national cultures free from extremism. The film was sure to receive cheers from middle-class viewers looking for reassurance about the course of their nation, especially when the girls prove that they are not lesbians and can work together with sensible (male) figures who appreciate their love of sports.

Thus, the tabloid press and many fans of the movie celebrate Bend it like Beckham as just a British (English) movie because it doesn’t focus on serious issues that may be exploited by “radicals”. As William Brown comments, Bend it like Beckham “does not make a big deal of any of the possible tensions in the film – be it racial, gender, generational, sexual. It is just a British film – something all too rare at the moment – and it gets on with telling the story, in the same way that Jess learns just to get on with the game. In the same way that the different characters just get on with each other (without having to “learn” this). It is by getting on that you win.”4

Indians and “true Brits” win in the “new Britain”, especially when they are just fed success stories. Along the lines of Robin Cook claiming, “Chicken Tikka Massala (a curry dish) is now a true British national dish, not only because it is the most popular, but because it is a perfect illustration of the way Britain absorbs and adapts external influences. Chicken Tikka is an Indian dish. The Massala sauce was added to satisfy the desire of British people to have their meat served in gravy,” Chadha believes “the success of the film represents the Indianizing of Britain, hybridization of Britain.”5

Bend it like Beckham has also been well received in Canada, not simply because of continued deference to “the motherland’s” (changing) tastes, but because of the desires of mainstream (middle class) individuals to move past (ignore) institutional racism. According to Now reviewers it is “churlish to hate on this movies winning formula”, because, as Chadha says, the film could refer to “people from the Caribbean in Toronto…That’s what the world is like these days. Most people live in cities that are diverse and environments that are culturally fluid.”6

An insistence that such films are universal ignores the fact that not everyone lives in suburbia. The majority of Toronto’s Caribbean population in Jane/Finch, Regent Park and Scarborough would certainly find it hard to see their homes replicated in the semi-detached south-east England on display in Bend it like Beckham. And here lies my problem with such attempts to build a middle class mosaic and pass them off as representing “the nation” or cosmopolitan cities throughout the world. Feel free to chronicle middle-class suburban life, but don’t claim they embody the “world today” or imply that their brand of cultural fusion represents a recent phenomenon. Such arrogant remarks by cosmopolitan city dwellers will not only receive attacks from the non-Western world, but also increase the alienation of working class “visible minorities” who have been living with diverse, culturally fluid areas in the West for centuries. Such working class ethnic minorities have long been living with “common sense, democratic racists”, although in the post-modern world their white antagonists can also find themselves outside the “new” national image.

In promoting Bend It Like Beckham, Chadha implores, “the film celebrates the processes of cultural change, the experience of living in a diverse environment from one generation to another and not only the difficulties involved but also the pleasures in becoming more integrated.”7 Yet surely the film shows that whites next door to a south-east Indian wedding celebration can continue to live in blissful ignorance of the party going on next door. Where interracial alliances are shown, we find the new lower-middle class in England comprising well-educated visible minorities reading The Guardian alongside the Del-boys (or Boycies) made good – white English (who are impressed by the respect for elders in “exotic” cultures) or Irish (who are allowed to – absurdly – explain that they understand what being called a “Paki” means) individualists from working class backgrounds.

Thus, in “new” Britain and Canada, economic rewards seem to be open for all. Non-white “achievers” can even obtain Mercedes and shop at trendy sports outlets so long as they restrain themselves, realize that “names can never hurt” them, and continue to offer nice food, while remaining apolitical and celebrate in national sports where whites have (recently and oh) so (goodness) graciously included them in the team. As soon as “they” begin “banging on about” more rights, and whites do not feel so willing to indulge in a bout of “liberal ecumenicism…as everyone comes to appreciate everyone else’s religion and tastes”,8 things might not be so rosy. When whites “own” traditions are felt to be under threat, when they don’t own their own semi-detached home to keep up with the Khans, we may understand the importance of Philip French’s comment: “the script by Chadha and her American husband, Paul Mayeda Berges (who also worked as second unit director), takes every easy way out and never recognises the possibility of real pain, the way the tougher, far funnier East Is East does.”9

Although it is unfortunate that reviewers feel compelled to compare East is East with Bend it like Beckham because they both document south Asians (even though East is East mainly dealt with Muslim communities, and Bend it like Beckham with Sikh communities), one should applaud the way East is East, while being based in Salford, Manchester, could offer laughter in pain, tackle the North and South of England, and comment on working class and middle class lives. It’s a shame that to be accepted as a truly national film, Bend it like Beckham had to try and assume that suburban south-east England = Britain, and that middle class suburbia (and truly awful nightclubs pumping out top 40 hits) = the West. The cultural landscapes of working-class and Northern communities also provide the opportunity to learn about cultural and ideological diversity, where, alongside council and social housing, underground dance music and high levels of racially mixed couples, there is also the pain of racial profiling and more overt opposition to integration (see the success of the far-right British National Party in Burnley and Oldham). The threat of racism and the far right may not be a “feel good” topic, but in flippantly dealing with (or entirely ignoring) such issues, Bend it like Beckham represents middle class disengagement, leaving working-class ethnic communities to fend for themselves, in the hope that talented working class individuals will simply “get on their bikes” and eventually offer them some exciting (but not too dangerous mind you) culture. Including some non-white colour (usually brown) into the national mosaic may help cool Britannia or mosaic images of Canada, but it doesn’t help those outside of suburbia fighting to build multiracial alliances.

“Multicultural” people in the West should not simply use a middle-class status to become “new” national citizens, employed to display the merits of “new” integration. Instead they must point to the cultural give and take displayed by multiracial working class communities such as Liverpool and Halifax, in the face of discrimination, for centuries. Class and racial discrimination remain issues that cannot be forgotten, because some whites and non-whites left out of the picture displayed on the big screen aren’t talking integration. Middle class folks might like to “see themselves” on screen, but perhaps they might also want to learn about the “Other” parts of their nations to stop the tabloid press condemning “scrounging” welfare recipients or immigrants. Engaging with angry white people worried about “new” immigrants, as well as the hybridity of working class youths, might not be “safe”. Yet one can’t just embrace the cultural integration of Bend It like Beckham or Ali G, feel pleased about the direction of one’s nations project to assimilate and learn from some (nice, funny, cuddly) non-whites, and then forget about the anguish that those without economic capital face when their working-class communities are left to suffer “misfortunes quietly, to slide into weariness and helplessness, and to be put out of sight.”10

Footnotes

1 Cameron Bailey, “Bend a Blast,” Now, March 6-12 2003.

2 Gurinder Chadha, “Call that a melting pot? America is still congratulating itself on its multicultural movie industry. But Britain is miles ahead,” The Guardian, April 11, 2002. http://film.guardian.co.uk/features/featurepages/0,4120,682376,00.html

3 Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian, April 12, 2002.

4 http://www.honestdog.com/may2002/films3.shtml

5 Cameron Bailey, “Bend a Blast.”

6 Adam Nayman, “She shoots, she scores”, Eye, March 6 2003.

7 Ibid.

8 Philip French, The Observer, April 14, 2002

9 Ibid.

10 P. J. Waller, “The Riots in Toxteth, Liverpool: A Survey” in New Community, IX, 3 1981/2, p. 352. Also see the left wing attack on multiculturalism as “taking black culture off the streets – where it had been politicised and…putting it in the council chamber, in the classroom and on the television, where it could be institutionalized, managed and reified…hindering rather than helping the fight against race and class oppressions”, see A. Kundnani, “The death of multiculturalism”, Commentary, Race and Class. http://www.irr.org.uk/cantle/index.htm

Author’s bio

Daniel McNeil is a graduate student at the University of Toronto. His research interests include observing how inclusive rooted or indigenous Black communities are of newer immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean, and looking at the rhetorical use of ‘Americanisation’ in Canada and the US.

by Daniel McNeil

- The Multiracial Activist – New People? New Politics? New Culture? A different kind of ‘Third Way’

- The Multiracial Activist – Finding a room for multiracial individuals: Selling Blackness in/as (post) modernity

- The Multiracial Activist – Me, We: individuality and social responsibility that knows no boundaries

- The Multiracial Activist – People who look like me

Copyright © 2003 Daniel McNeil and The Multiracial Activist. All rights reserved.

One comment