Rivonia’s Children

Three Families and the Cost of Conscience in White South Africa

by Glenn Frankel

Published by Farrar Straus & Giroux; 0374250995; $25.00US; Aug. 99

Rivonia’s Children is the harrowing and inspiring account of a handful of white activists, many of them Jewish, who risked their lives to combat apartheid when, in the 1960s, South Africa plunged into an era of darkness from which it has only recently emerged.

This is the story of Hilda and Rusty Bernstein, longtime communists so deeply committed to the cause that even the threat of life imprisonment did not stop them; of Ruth First, a fiery activist arrested and held for months without charge; and of AnnMarie Wolpe, an innocent bystander sucked into the maelstrom, who had to decide whether to risk her own freedom and the life of her sick infant by helping her activist husband escape from prison.

Their underground headquarters was in Rivonia, a Johannesburg suburb, and it was there that their dream of revolution was shattered after a police raid in 1963. Nelson Mandela, Rusty Bernstein, and eight of their comrades were tried for sabotage and attempting to violently overthrow the government. The Rivonia raid not only destroyed an old order of benign radicalism but thrust radicals into a new, dangerous world of action, leading to the Soweto uprising and the birth of another generation of black activists. The regime turned a corner as well, becoming a full-scale police state that waged a dirty war of brutality and oppression. In the end, freedom triumphed, and the sacrifices of this small group of whites contributed to the miracle of racial reconciliation that is the new South Africa.

The searing tale of soaring hopes and ideals betrayed, Rivonia’s Children is also the moving story of the impact of political activism on the lives of three families.

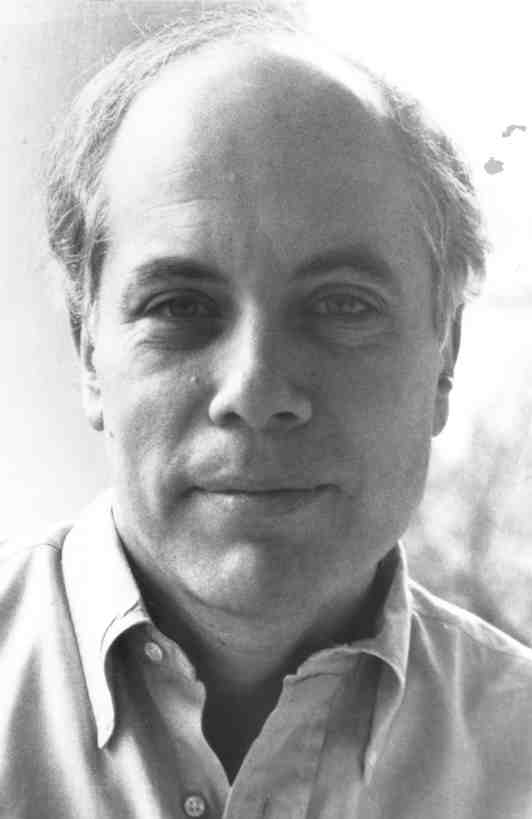

Author

Glenn Frankel has been a staff writer and editor for The Washington Post for twenty years. He is the paper’s former bureau chief in South Africa, London, and Jerusalem, where he won the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for his coverage of the Middle East. He is the author of Beyond the Promised Land: Jews and Arabs on the Hard Road to a New Israel, winner of the 1995 National Jewish Book Award. Frankel is currently the editor of The Washington Post Magazine and lives with his family in Arlington, Virginia.

Excerpt

The following is an excerpt from the book: Rivonia’s Children: Three Families and the Cost of Conscience in White South Africa by Glenn Frankel

Published by Farrar Straus & Giroux; 0374250995; $25.00US; Aug. 99

Copyright © 1999 Glenn Frankel

THE RAID

Communists are the last optimists.

Nadine Gordimer

Burger’s Daughter

JOHANNESBURG, JULY 11, 1963

He was late.

Under normal circumstances, she would have considered it a minor annoyance, a matter of a dinner grown cold, or a delay in helping the children with their homework, or an errand that might not get run for another day. Nothing to worry about. Under normal circumstances.

He had left the house just before noon in the black Chevrolet sedan. “I’m going in to report, he told her. “Then I have to deliver some drawings. And this afternoon I’ll be busy.”

She knew the routine. For nine months, ever since the Justice Ministry’s written order restricting his movements, it had been a daily part of their lives. First he would drive downtown past the gleaming office towers and unruly markets of bustling Johannesburg, past Greaterman’s department store, the Sanlam insurance building and the Chamber of Mines, to the red-brick police station at Marshall Square, a squat, brooding fortress that dated back to the turn of the century when Johannesburg was little more than an overgrown mining camp. He would park on the street and march briskly to the tall, studded doors that served like a gate to a forbidden castle. Inside, he would enter the charge office, where the desk sergeant would open the oversized ledger book to the current page, rotate its spine so that it faced him, and produce a pen. Other than a terse “Good afternoon,” no words would be spoken; both the sergeant and he knew why he was there. He would sign his name on the first blank line, then return the book to the desk man, who would record the date and time next to the signature. Within minutes he would be back inside the safety of the Chevy and drive off, having once again fulfilled the condition of his daily house arrest.

It was a bloodless, seemingly painless ritual, yet he dreaded each trip to Marshall Square. Every time he walked into the station, he feared he would not walk out again. Sooner or later, he believed, the state would stop toying with him and relegate him to the ranks of the disappeared. The thought of it made his knees buckle and left him in a cold sweat even on the coolest winter day. Marshall Square would swallow him up and bury him in a prison cell tomb deep within its bowels, a place from which he might never return.

But not today. After the mandatory visit he attended to the work he was responsible for as an architect, visiting an engineer, helping him with a project. There had been a time when such tasks would have taken most of the day. But in recent years, as the authorities graced him with their very special attention and he spent more and more time in court fending off their accusations, commissions had dried up, leaving him with little professional work and a shrinking income to support a family of six. Now, on most days, it only took him a few minutes to deal with the work.

After that he headed somewhere else, somewhere secret, to engage in the illegal political work that had led to his house arrest and that, if he were caught, could land him in prison for a very long time.

Under the terms of his restriction, he was required to be home by six-thirty each night and remain there until six-thirty the next morning. If he missed the deadline, even by a minute, he risked a fine and imprisonment. A few times he had cut it close, most recently a few days earlier when a long and cantankerous political dispute had spilled over into the early evening. But he was a cautious man by nature–serious, quiet and responsible, and not inclined to give his wife and children more to worry about than they already had. Usually it was safely before six when she would hear the familiar rumble of the Chevy as he eased into the driveway, and she would start to breathe again. But not tonight.

“I’ll be busy,” he had said that morning, and she had not asked to be told more. She knew by his very terseness that he would be doing something for the movement. He never told her exactly what or where. This deliberate vagueness was designed to protect them both–she could not divulge what she did not know. Still, she suspected that he was going to Lilliesleaf, a farm north of the city in the suburb of Rivonia. The movement had purchased the twenty-eight-acre estate clandestinely two years earlier, set up one of its members as owner and used it as a secret headquarters for men who were plotting sabotage attacks against the state. All of this she knew and much, much more, all of it guilty and very dangerous knowledge, and it made her uneasy. They both knew Rivonia was not a secure location, that too many people who were under suspicion came and went from there, traveling mostly in their own cars with license plate numbers that the Special Branch men seemed to know by heart. He had complained often about the lack of security, and he had promised her that he would stop going there, but there always seemed to be one last matter that had to be discussed, one last meeting that had to be attended. So far they had been lucky. But they both knew it would not last forever.

They had been married for nearly twenty-two years and they had worked together as comrades in the Communist Party for even longer. Still, there were things they never said to each other, feelings they did not share. That morning she had wanted to plead with him not to go, to tell him it was too dangerous to keep taking such risks at a time when the police were looking for any excuse to strike. But she did not do so, partly because her own years of political discipline had conditioned her to endure stoically, and partly because she knew he would not heed her plea. He understood the dangers as keenly as she did, felt the same turbulent anxiety in the pit of his stomach. Yet he had decided to take the risk. It was a decision she knew she must honor even as she dreaded its potential consequences. “Take care of yourself… Be careful.” That was all she said.

She knew the risks so intimately because she was taking many of them herself. Despite the security crackdown, she still attended secret meetings, working to keep alive banned organizations and helping arrange illegal activities such as protest demonstrations and boycotts. Increasingly she could see something many of her comrades refused to admit: that what they were doing was futile. The government was slowly transforming itself into a police state. There were new laws restricting their movements and further contracting their already limited freedoms, and the police were coming down on them with a weight they had never felt before. The few whites like themselves who stood with Nelson Mandela and the black liberation movement were reeling from the pressure and the blows. They had long grown used to the sense that someone was always watching or listening. But now it had gone far beyond that. People were disappearing, swept away in mass raids or sucked into the bottomless pit of recurring ninety-day detentions. Like Germany before World War II, South Africa seemed gripped by a mass fever of desperation and fatalism. Each night they listened for the sound of cars pulling up the drive, footsteps on the pavement and a knock on the door. Their personal lives were not immune to these fears; their own children had become hostages to their cause. Even the house that they had cherished and raised their family in for fifteen years seemed to turn against them.

It was a modest four-bedroom cottage in a leafy, backwoods neighborhood just a ten-minute drive from downtown–154 Regent Street in the eastern suburb of Observatory. There was no thatched roof or split-level flourishes, just a rust-colored, triangular roof of corrugated tin atop a plain, whitewashed, one-story building whose walls always seemed in need of paint. There was a small swimming pool out back where the children seemed to live day and night in summer. But the trees were the real prize. They graced both the front and back, ranging from the six great jacarandas that lined the driveway to the clusters of lemon, fig, apricot, quince, wattle, apple, peach and plum trees scattered throughout the grounds, to the vine that yielded black grapes in summer. Their daughter Frances, who had just turned twelve, thought of it as her own little Garden of Eden, a perfect African paradise. The back yard was not large, but it sloped downward to merge with several others in a long, continuous field with only a low wire fence separating them. The ground was hard and dry and brittle as bone in winter, but the powerful summer rains softened and massaged it and coaxed dark sweet smells from the rich red earth.

When they first lived there, doors and windows had seldom been closed even in winter. Children paraded through both day and night on their way to someone or somewhere. Visitors, whether white, black or Indian–an unusually free mix in a society where race was the ironclad organizing principle of human existence–came and went without ringing the bell. They swam, sat, talked, stayed for tea. And like most white South Africans, they had African servants, Bessie and Claude, to help with domestic chores and child care.

Later she would write that she felt as if the house was itself a living organism; it breathed and murmured and rattled and groaned, and it embraced them in its gentle warmth. But the very openness of the house became a weapon in the hands of the police. Inside, no one could hide from view; onlookers from without could see easily through the glazed windows. Secrets could not be told, nor kept. The phone, too, be- came an enemy. They assumed it was wired to record not only their phone calls but other conversations as well. Over and over they drilled the rules into their children like a catechism of fear: Never tell callers that we’re out, never ever say where we’ve gone or when we’ll be back. It got so bad that the children dreaded hearing the phone ring.

Her husband was an amateur carpenter–he designed a false bottom for her desk, a secret panel for the drying rack in the kitchen and special slots at the top of the kitchen door and the linen cupboard. In these ordinary icons of domestic life, the two of them concealed notes of meetings, forbidden magazines and other documents whose possession could land them a year or more behind bars. They stashed a list of names and numbers as well, far from the prying eyes of police who longed to discover it and whose invasions of their house and their privacy had become more and more frequent. Nothing was off-limits to these officers of the law–the master bedroom, the children’s rooms, even the bathroom were all considered open territory to be scrutinized, pawed through and ransacked with contemptuous familiarity.

There were times when she longed for a normal middle-class life, times when she wanted to chuck it all and flee for the nearest border, as many of their closest friends were doing. The Hodgsons had fled, the Bermans too. Joe Slovo, Yusuf Dadoo, J.B. Marks, Moses Kotane and countless others had left on secret missions and never come back. She could feel their pull. But she was too committed, not just to the movement but to her comrades, the handful of people who were as deeply involved as she and her husband. They were like a second family to her; she could no more abandon them than she could her own children. To cut off contact now, to give up in the face of the state’s terrible power, would be an act of betrayal not only of her closest friends but of herself. Besides, as strong as she was, he was even stronger and more determined not to cut and run.

July was the first full month of winter south of the equator, and the African sun set abruptly each night with a brilliant display of crimson defiance. Most nights this glorious ritual gave her strength, but tonight, she would recall later, it only compounded her sense of dread as the time passed and still he did not return. There was nowhere to call, no one to ask, no way to reach him. She could only sit and wonder and wait. As she started preparing dinner, she tried not to look at the kitchen wall clock, but she knew that the sun went down just before six. By six- fifteen the darkness was complete, the night like a lid sealing in her fear. There was no way to see from the window if a police car was hovering up the block. She could send one of the children to sneak a look, but that might alert the security men that something was wrong. It might also alarm the children, whose keen antennae were already sensing her anxiety. Toni, at nineteen the eldest, sat quietly with a friend in the living room before a roaring fire. “Daddy’s late” she said matter-of-factly. Patrick, fifteen, sullen and withdrawn, was away at a holiday camp where he tried to escape from the relentless claustrophobia of his parents and their politics. Frances, who was scholarly, dutiful and sincere, was spending the night at a friend’s house, while Keith, six, coughed and sniffled, the first signs of a new bout of the septic throat that often kept him awake through the night.

She looked up again. It was six twenty-nine, and she watched the second hand sink to the bottom of the clock and then begin to climb. If something had happened at Rivonia, she knew that their world would come crashing down. All the troubles they had faced in the past would be nothing compared to what was to come. Then six-thirty came and went, and Hilda Bernstein knew. Her husband Rusty would not be coming home. Not that night. Not for many nights to come..

Copyright © 1999 Glenn Frankel and The Multiracial Activist {jos_sb_discuss:9}