Catfish and Mandala: A Two-Wheeled Voyage Through the Landscape and Memory of Vietnam

by Andrew X. Pham

Published by Farrar Straus & Giroux; 0-374-11974-0; $25.00US; Sept. 1999

Catfish and Mandala is the poignant, lyrical tale of an American odyssey–a solo bicycle voyage around the Pacific Rim to Vietnam–made by a young Vietnamese-American man in pursuit of both his adopted homeland and his forsaken fatherland. Intertwined with an often humorous travelogue spanning a year of discovery is a memoir of war, escape, and, ultimately, family secrets.

Viewed through Viet-kieu (foreign Vietnamese) eyes and told in an accomplished voice, Catfish and Mandala uncovers a new Vietnam, its scarred landscape dotted with indefinable, tenacious people grappling with their unique brand of Third World capitalism. Their stories are at once ephemeral and lasting, their faces fleeting, intense, memorable. There is Pham’s stepgrandfather Le, the fish-sauce baron of Phan Thiet, who claims his ancestors invented the condiment; his father, a POW of the Vietcong, who finally leads his family on a perilous boat journey to the land of their freedom; and his beloved sister, Chi, a post-operative transsexual who commits suicide.

Pham deftly limns the lasting scars of the Vietnam War and the plight of a refugee family, to create a haunting portrait of Americaframed by the perspective of an outsider, a stranger straddling two continents.

In Vietnam, he’s taken for Japanese or Korean by his countrymen, except by his relatives, who doubt that as a Vietnamese he has the stamina to complete his journey (“Only Westerners can do it”). And in the United States, of course, he’s considered anything except American.

A vibrant, picaresque memoir written with narrative flair and a wonderful, eye-opening sense of adventure, Catfish and Mandala is an unforgettable search for cultural identity and a moving exploration of memory by a striking new voice in American letters.

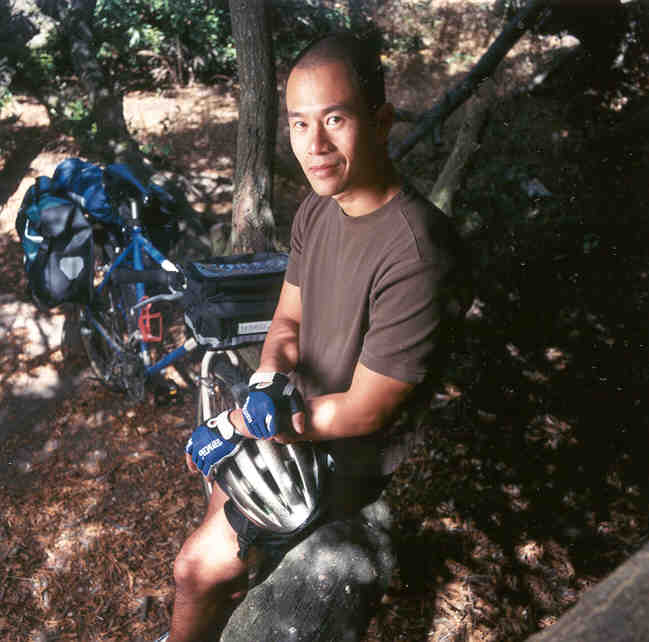

Author

Andrew X. Pham was born in Vietnam in 1967 and moved to California with his family after the war. He lives in Portland, Oregon. This is his first book.

Excerpt

The following is an excerpt from the book: Catfish and Mandala: A Two-Wheeled Voyage Through the Landscape and Memory of Vietnam by Andrew X. Pham

Published by Farrar Straus & Giroux; 0-374-11974-0; $25.00US; Sept. 99

Copyright © 1999 Andrew X. Pham

Exile-Pilgrim

The first thing I notice about Tyle is that he can squat on his haunches Third World-style, indefinitely. He is a giant, an anachronistic Thor in rasta drag, bare-chested, barefoot, desert-baked golden. A month of wandering the Mexican wasteland has tumbled me into his lone camp warded by cacti. Rising from the makeshift pavilion staked against the camper top of his pickup, he moves to meet me with an idle power I envy. I see the wind has carved leathery lines into his legend-hewn face of fjords and right angles.

In a dry, earthen voice, he asks me, “Looking for the hot spring?”

“Yeah, Agua Caliente. Am I even close?”

“Sure. This is the place. Up the way a couple hundred yards.”

“Amazing! I found it!”

He smiles, suddenly very charismatic, and shakes his head of long matty blond hair. “How you got here on that bike is amazing.”

I had been pedaling and pushing through the forlorn land, roaming the foreign coast on disused roads and dirt tracks. When I was hungry or thirsty, I stopped at ranches and farms and begged the owners for water from their wells and tried to buy tortillas, eggs, goat cheese, and fruit. Every place gave me nourishment; men and women plucked grapefruits and tangerines from their family gardens, bagged food from their pantries, and accepted not one peso in return. Why, I asked them. Señor, they explained in the patient tone reserved for those convalescing, you are riding a bicycle, so you are poor. You are in the desert going nowhere, so you are crazy. Taking money from a poor and crazy man brings bad luck. All the extras, they confided, were because I wasn’t a gringo. A crew of Mexican ranchers said they liked me because I was a bueno hermano–good brother–a Vietnamito, and my little Vietnam had golpea big America back in seventy-five. But I’m American, Vietnamese American, I shouted at them. They grinned–Si, si, Señor–and grilled me a slab of beef.

Tyle says, “So, where are you from?”

“Bay Area, California.”

“No. Where are you from? Originally.”

I have always hated this question and resent him for asking. I hide my distaste because it is un-American. Perhaps I will lie. I often do when someone corners me. Sometimes, my prepared invention slips out before I realize, it: I’m Japanese-Korean-Chinese-mixed-race Asian. No, sir, can’t speak any language but good old American English.

This time, I turn the question: “Where do you think?”

“Korea.”

Something about him makes me dance around the truth. I chuckle, painfully aware that “I’m an American” carries little weight with him. It no doubt resonates truer in his voice.

The blond giant holds me with his green eyes, making me feel small, crooked. So, I reply, “We nips all look alike.”

But it isn’t enough. He looks the question at me again, and, by a darkness on his face, I know I owe him.

“I’m from Vietnam.”

A flinch in the corner of his eye. He grunts, a sound deep from his diaphragm. Verdict passed. He turns his back to me and heaves into the cactus forest.

I stand, a trespasser in his camp, hearing echoes–Chink, gook, Jap, Charlie, GO HOME, SLANT-EYES!–words that, I believe, must have razored my sister Chi down dark alleys, hounded her in the cold after she had fled home, a sixteen-year-old runaway, an illegal alien without her green card. What vicious clicking sounds did they make in her Vietnamese ears, wholly new to English? And, within their boundaries, which America did she find?

A man once revealed something which disturbed me too much to be discounted. He said, “Your sister died because she became too American.”

Later in the night, from the thick of the brush, Tyle ghosts into the orange light of my campfire. He nods at me and folds himself cross-legged before the popping flames, uncorks a fresh tequila bottle, takes a swig, and hands it to me. We sit on the ground far apart enough that with outstretched arms we still have to lean to relay the bottle.

I grip the warm sand between my toes and loll the tart tequila on my tongue. A bottom-heavy moon teeters on the treetops. Stars balm the night. We seem content in our unspoken truce.

When the bottle is half empty, Tyle begins to talk. At first, he talks about the soothing solitude of the Mexican desert. Life is simple here, food cheap, liquor plentiful. He earns most of his money from selling his handicrafts–bracelets, woven bands, beads, leather trinkets–to tourists. When times are tough, there are always a few Mexicans who will hire him for English lessons or translations. And the border isn’t too far if he needs to work up a large chunk of cash. Between the mundane details, his real life comes out obliquely. Tyle has a wife and two boys. He has been away from them nine years. I am the first Vietnamese he has seen since he fled to Mexico seven years ago.

When four fingers of tequila slosh at the bottom of the bottle, he asks me, “Have you been back to Vietnam?”

“No. But someday I’ll go back … to visit.”

Many Vietnamese Americans “have been back.” For some of us, by returning as tourists we prove to ourselves that we are no longer Vietnamese but Vietnamese Americans. We return, with our hearts in our throats, to taunt the Communist regime, to show through our material success that we, the once pitiful exiles, are now the victors. No longer the poverty-stricken refugees clinging to fishing boats, spilling out of cargo planes onto American soil, a mess of open-mouthed terror, wide-eyed awe, hungry and howling for salvation. Time has veiled the days when America fished us out of the ocean like drowning cockroaches and fed us and clothed us–we, the onus of their tragedy. We return and in our personal silence, we gloat at our conquerors, who now seem like obnoxious monkeys cheating over baubles, our baggage, which mean little to us. Mostly, we return because we are lost.

Tyle says, “I was in Nam.”

I have guessed as much. Not knowing what to say, I nod. Vets–acquaintances and strangers–have said variations of this to me since I was a kid and didn’t know what or where Nam was. The contraction was lost on a boy struggling to learn English. But the note, the way these men said it, told me it was important, someplace I ought to know. With the years, this statement took on new meanings, each flavored by the tone of the speaker. There was bitterness, and there was bewilderment. There was loss and rage and every shade of emotion in between. I heard declarations, accusations, boasts, demands, obligations, challenges, and curses in the four words: I was in Nam. No matter how they said it, an ache welled up in me until an urge to make some sort of reparation slicked my palms with sweat. Some gesture of conciliation. Remorse. A word of apology.

He must have seen me wince for he says it again, more gently.

At that, I do something I’ve never done before. I bow to him like a respected colleague. It is a bow of acknowledgment, a bow of humility, the only way I can tell him I know of his loss, his sufferings.

Looking into the fire, he says softly, “Forgive me. Forgive me for what I have done to your people.”

The night buckles around me. “What, Tyle?”

“I’m sorry, man. I’m really sorry,” he whispers. The blond giant begins to cry, a tired, sobless weeping, tears falling away untouched. My mouth forms the words, but I cannot utter them. No. No, Tyle. How can I forgive you? What have you done to my people? But who are my people? I don’t know them. Are you my people? How can you be my people? All my life, I’ve looked at you sideways, wondering if you were wondering if my brothers had killed your brothers in the war that made no sense except for the one act of sowing of me here–my gain–in your bed, this strange rich-poor, generous-cruel land. I move through your world, a careful visitor, respectful and mindful, hoping for but not believing in the day when I become native.. I am the rootless one, yet still the beneficiary of all of your and all of their sufferings. Then why, of us two, am I the savior, and you the sinner?

“Please forgive me.

I deny him with my silence.

His Viking face mashes up, twisting like a child’s just before the first bawl. It doesn’t come. Instead words cascade out, disjointed sentences, sputtering incoherence that at the initial rush sound like a drunk’s ravings. Nameless faces. Places. Killings. He bleeds it out, airs it into the flames, pours it on me. And all I can do is gasp Oh, God at him over and over, knowing I will carry his secrets all my days.

He asks my pardon yet again, his open hand outstretched to me. This time the quiet turns and I give him the absolution that is not mine to give. And, in my fraudulence, I know I have embarked on something greater than myself.

“When you go to Vietnam,”‘ he says, stating it as a fact, “tell them about me. Tell them about my life, the way I’m living. Tell them about the family I’ve lost. Tell them I’m sorry.”

I give Tyle the most honored gift, the singular gift we Vietnamese give best, the gift into which one can cast all one’s sorrow like trash into an abyss, only sometimes the abyss lies inside the giver. I give him silence.

- Purchase a copy of Catfish and Mandala

Copyright © 1999 Andrew X. Pham and The Multiracial Activist