Devoutly dividing us

Opponents of interracial marriage say God is on their side

By Phillip W. D. Martin, 11/07/99

Boston Globe The following article, from the Online edition of the Boston Globe, details how some Americans feel about interracial marriages thirty years after the Loving landmark case.

There is only one state in the country that still bans interracial marriage and, if the polls are right, a majority of Alabama voters will vote next year to repeal that statute.

But about a third of them are expected to vote against repeal, just as a third of South Carolinians voted unsuccessfully last year to keep their state’s ban. Both states mirror the nation as a whole: Polls show that between a quarter and a third of us oppose the marriage of whites to blacks.

It is telling that most Alabamians opposed to interracial marriage identify themselves as evangelical Christians, according to a poll by the Alabama Educational Association. They say they believe that such relationships contravene the word of God.

Indeed, religion is among the most enduring rationales for the remaining opposition to interracial marriages. As outright racism – ”I don’t like blacks” or ”blacks are inferior” – has become less pronounced publicly, and as statutes banning interracial marriage have been overturned, religious arguments against mixing the races are being called up in their place.

While evoking ”God’s will” may seem a more socially acceptable way to divide us, it’s effect is the same. The words of state Representative Lanny Littlejohn of Spartenburg, S.C., capture the sentiment. Asked about interracial marriage, he responds: ”That’s not what God intended when he separated the races back in the Babylonian days. The races would be a lot better off if they stuck with their own kind.

”I been raised a Baptist all my life, and I guess that’s exactly where it comes from. My family taught me that over the years, and that didn’t take place during my upbringing, and therefore I don’t espouse it.”

Beliefs such as Littlejohn’s are not limited to Southern Baptists.

”It’s a complex doctrine that can’t be isolated in any one denominational strain,” says Alan Callahan, a professor of theology at Harvard Divinity School and an ordained Baptist minister. ”It circulates within American evangelical religions; generally, it cuts a broad swath of religion in America.”

Any prohibitions – religious or otherwise – against interracial relationships would seem moot in 1999, 32 years after the US Supreme Court’s landmark decision known as Loving v. Virginia. In the middle of the night on July 11, 1958, Richard Loving, who is white, and his African-American wife, Mildred, were rousted from their bed and arrested in Caroline County, Va.

Soon afterward a Virginia judge ruled their marriage illegal and added, ”Almighty God created the races … and the fact that He separated the races showed that He did not intend for the races to mix.” The Supreme Court ruled otherwise.

But today, three decades later, a sizable percentage of Americans continue to be skeptical about mixed marriages. A Washington Post poll conducted last summer revealed that 1 in 4 Americans still found marriages between blacks and whites ”unacceptable.”

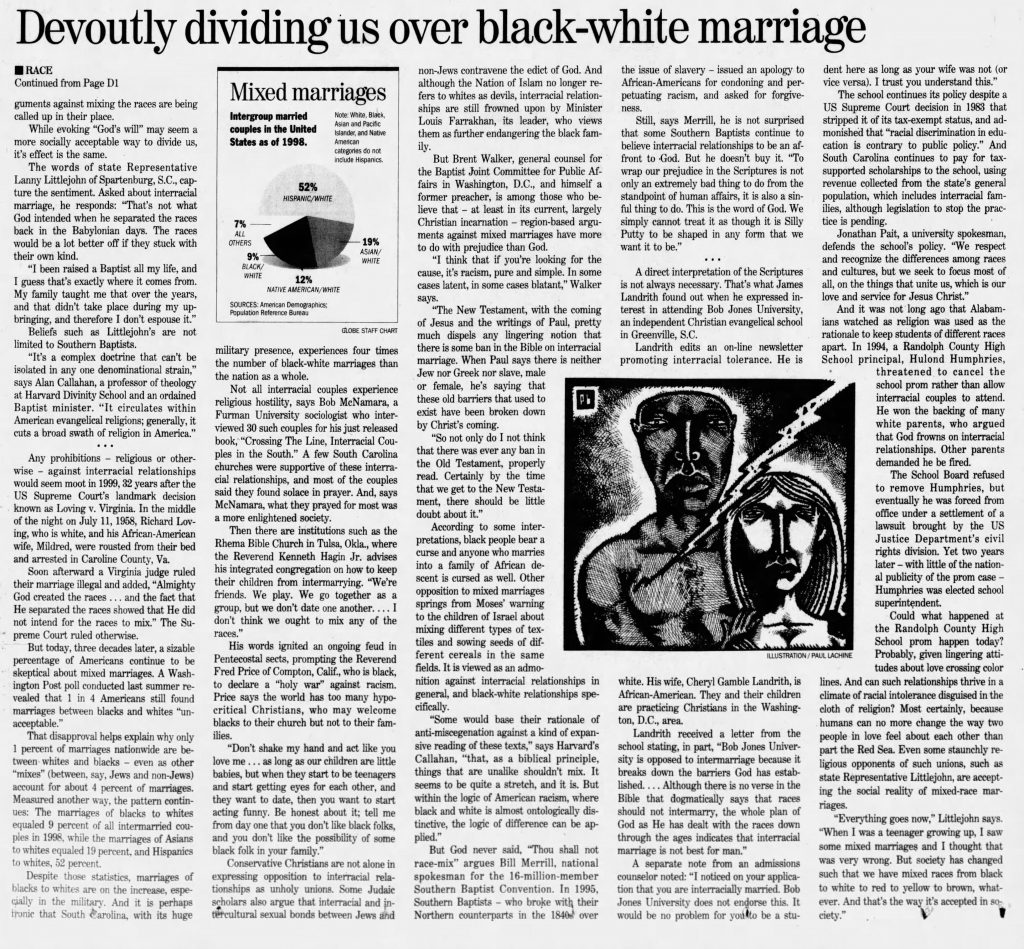

That disapproval helps explain why only 1 percent of marriages nationwide are between whites and blacks – even as other ”mixes” (between, say, Jews and non-Jews) account for about 4 percent of marriages. Measured another way, the pattern continues: The marriages of blacks to whites equaled 9 percent of all intermarried couples in 1998, while the marriages of Asians to whites equaled 19 percent, and Hispanics to whites, 52 percent.

Despite those statistics, marriages of blacks to whites are on the increase, especially in the military. And it is perhaps ironic that South Carolina, with its huge military presence, experiences four times the number of black-white marriages than the nation as a whole.

Not all interracial couples experience religious hostility, says Bob McNamara, a Furman University sociologist who interviewed 30 such couples for his just released book, ”Crossing The Line, Interracial Couples in the South.” A few South Carolina churches were supportive of these interracial relationships, and most of the couples said they found solace in prayer. And, says McNamara, what they prayed for most was a more enlightened society.

Then there are institutions such as the Rhema Bible Church in Tulsa, Okla., where the Reverend Kenneth Hagin Jr. advises his integrated congregation on how to keep their children from intermarrying. ”We’re friends. We play. We go together as a group, but we don’t date one another. … I don’t think we ought to mix any of the races.”

His words ignited an ongoing feud in Pentecostal sects, prompting the Reverend Fred Price of Compton, Calif., who is black, to declare a ”holy war” against racism. Price says the world has too many hypocritical Christians, who may welcome blacks to their church but not to their families.

”Don’t shake my hand and act like you love me … as long as our children are little babies, but when they start to be teenagers and start getting eyes for each other, and they want to date, then you want to start acting funny. Be honest about it; tell me from day one that you don’t like black folks, and you don’t like the possibility of some black folk in your family.”

Conservative Christians are not alone in expressing opposition to interracial relationships as unholy unions. Some Judaic scholars also argue that interracial and intercultural sexual bonds between Jews and non-Jews contravene the edict of God. And although the Nation of Islam no longer refers to whites as devils, interracial relationships are still frowned upon by Minister Louis Farrakhan, its leader, who views them as further endangering the black family.

But Brent Walker, general counsel for the Baptist Joint Committee for Public Affairs in Washington, D.C., and himself a former preacher, is among those who believe that – at least in its current, largely Christian incarnation – region-based arguments against mixed marriages have more to do with prejudice than God.

”I think that if you’re looking for the cause, it’s racism, pure and simple. In some cases latent, in some cases blatant,” Walker says.

”The New Testament, with the coming of Jesus and the writings of Paul, pretty much dispels any lingering notion that there is some ban in the Bible on interracial marriage. When Paul says there is neither Jew nor Greek nor slave, male or female, he’s saying that these old barriers that used to exist have been broken down by Christ’s coming.

”So not only do I not think that there was ever any ban in the Old Testament, properly read. Certainly by the time that we get to the New Testament, there should be little doubt about it.”

According to some interpretations, black people bear a curse and anyone who marries into a family of African descent is cursed as well. Other opposition to mixed marriages springs from Moses’ warning to the children of Israel about mixing different types of textiles and sowing seeds of different cereals in the same fields. It is viewed as an admonition against interracial relationships in general, and black-white relationships specifically.

”Some would base their rationale of anti-miscegenation against a kind of expansive reading of these texts,” says Harvard’s Callahan, ”that, as a biblical principle, things that are unalike shouldn’t mix. It seems to be quite a stretch, and it is. But within the logic of American racism, where black and white is almost ontologically distinctive, the logic of difference can be applied.”

But God never said, ”Thou shall not race-mix” argues Bill Merrill, national spokesman for the 16-million-member Southern Baptist Convention. In 1995, Southern Baptists – who broke with their Northern counterparts in the 1840s over the issue of slavery – issued an apology to African-Americans for condoning and perpetuating racism, and asked for forgiveness.

Still, says Merrill, he is not surprised that some Southern Baptists continue to believe interracial relationships to be an affront to God. But he doesn’t buy it. ”To wrap our prejudice in the Scriptures is not only an extremely bad thing to do from the standpoint of human affairs, it is also a sinful thing to do. This is the word of God. We simply cannot treat it as though it is Silly Putty to be shaped in any form that we want it to be.”

A direct interpretation of the Scriptures is not always necessary. That’s what James Landrith found out when he expressed interest in attending Bob Jones University, an independent Christian evangelical school in Greenville, S.C.

Landrith edits an on-line newsletter promoting interracial tolerance. He is white. His wife, Cheryl Gamble Landrith, is African-American. They and their children are practicing Christians in the Washington, D.C., area.

Landrith received a letter from the school stating, in part, ”Bob Jones University is opposed to intermarriage because it breaks down the barriers God has established. … Although there is no verse in the Bible that dogmatically says that races should not intermarry, the whole plan of God as He has dealt with the races down through the ages indicates that interracial marriage is not best for man.”

A separate note from an admissions counselor noted: ”I noticed on your application that you are interracially married. Bob Jones University does not endorse this. It would be no problem for you to be a student here as long as your wife was not (or vice versa). I trust you understand this.”

The school continues its policy despite a US Supreme Court decision in 1983 that stripped it of its tax-exempt status, and admonished that ”racial discrimination in education is contrary to public policy.” And South Carolina continues to pay for tax-supported scholarships to the school, using revenue collected from the state’s general population, which includes interracial families, although legislation to stop the practice is pending.

Jonathan Pait, a university spokesman, defends the school’s policy. ”We respect and recognize the differences among races and cultures, but we seek to focus most of all, on the things that unite us, which is our love and service for Jesus Christ.”

And it was not long ago that Alabamians watched as religion was used as the rationale to keep students of different races apart. In 1994, a Randolph County High School principal, Hulond Humphries, threatened to cancel the school prom rather than allow interracial couples to attend. He won the backing of many white parents, who argued that God frowns on interracial relationships. Other parents demanded he be fired.

The School Board refused to remove Humphries, but eventually he was forced from office under a settlement of a lawsuit brought by the US Justice Department’s civil rights division. Yet two years later – with little of the national publicity of the prom case – Humphries was elected school superintendent.

Could what happened at the Randolph County High School prom happen today? Probably, given lingering attitudes about love crossing color lines. And can such relationships thrive in a climate of racial intolerance disguised in the cloth of religion? Most certainly, because humans can no more change the way two people in love feel about each other than part the Red Sea. Even some staunchly religious opponents of such unions, such as state Representative Littlejohn, are accepting the social reality of mixed-race marriages.

”Everything goes now,” Littlejohn says. ”When I was a teenager growing up, I saw some mixed marriages and I thought that was very wrong. But society has changed such that we have mixed races from black to white to red to yellow to brown, whatever. And that’s the way it’s accepted in society.”

Copyright 1999 The Boston Globe