Racial identities spawn new terminology: Are you Melungeon, Nuyorican or what?

Wednesday, March 08, 2006

By Mackenzie Carpenter,

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

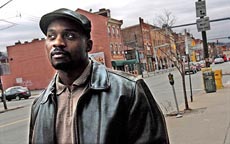

When Lamaas Bey is asked his race on a form or survey, he doesn’t check the box that says black or African-American, even though many people think that’s what he is.

Lamaas Bey, a program manager at the Urban League, identifies himself as either “Asiatic” or “Moorish American.”

Click photo for larger image.

Instead, the 27-year-old Homewood resident writes in the word “Asiatic,” because, he says, “I’m going back to the cradle of civilization where the first people came from, which was the continent of Asia. The whole world at one time was connected, and it was called Asia.”

Mr. Bey is only one of many people who have decided that calling themselves black, white or Asian is no longer enough, given the kaleidoscopic possibilities of racial identity today.

James Landrith, the Virginia-based creator of the Web site Multiracial.com, says he’s of “Melungeon” descent, which he describes as a mix of black, white and Native Americans from the Appalachian region. Malcolm Jones, who grew up in Mt. Lebanon and now lives in California, considers himself white, but is frequently mistaken as Latino or Native American; as a child his Japanese mother and Swedish-American father jokingly called him “Swedenese.”

On the Internet, Blasian.com caters to those who consider themselves a mix of black and Asian; Jamericanoutreach.com is a charity founded by Jamaican-American immigrants who refer to themselves as “Jamericans”; Nuyorican.org is a multicultural arts site with a focus on the “Nuyorican” community, defined by Wikipedia as “a blending of the phrases ‘New York’ and ‘Puerto Rican’ and refers to the members or culture of the Puerto Rican diaspora located in or around New York City.”

If it seems that young people, especially, are opting for the multiracial label, there’s a simple explanation why.

“Society is more diverse today than it was 20 or 30 years ago,” says Terrell Jones, vice provost for educational equity at Penn State University, noting that between 5 percent to 10 percent of the students in his classes define themselves as multiracial. That, in part, is because of the jump in the number of interracial marriages from 1 percent of the population to at least 5 percent since 1967, when the Supreme Court ruled antimiscegenation laws unconstitutional.

Today, there are more and more people like Manuel Zaniga, 30, of Squirrel Hill. His background is Filipino and Japanese, while his wife is of German and Dutch descent. Their newborn baby boy, he says, could grow up identifying himself as “mestiso” — a term meaning Filipino mixed with another race — or Asian-American, as Mr. Zaniga identifies himself. Still another option is the term, “Hapa,” which used to refer to those with Hawaiian blood mixed with other races, but it now is used more broadly to refer to those born around the Pacific rim.

“My wife and I have been talking about how we’ll broach the subject with him when he’s older,” Mr. Zaniga says. “A lot of it has to do with what he wants.”

Changing the Census

Until 2000, the Census required people to check off only one box among several mutually exclusive racial categories — black, white, Asian and Pacific Islander, Native American and “other.” Then, after strong lobbying by advocates for multiracial groups, that requirement was changed to allow people to check off as many boxes as they wanted.

Originally, those groups had wanted a box marked “multiracial,” but that idea was strongly opposed by a variety of civil rights groups, fearful of a dilution of political power that could affect the allocation of federal aid dollars, as well as law and voting rights enforcement. Gary Flowers, then-director of the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under the Law, compared such a box to “apartheid,” arguing that it would dilute the strength of the African-American community, a position backed by the Hispanic group La Raza.

So, a compromise was reached: Census respondents could fill out as many boxes as they wished. Consequently, in 2004, the U.S. Census Bureau found that nearly half of all Americans who identified themselves as being members of more than one race — about 4.4 million in all — were under age 18.

There’s other evidence that this move toward self-identification is generational. A study by Maria Root, a Seattle-based clinical psychologist and author of “The Multiracial Experience,” found that biracial people born before the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s tended to identify themselves as black, while those born during or after that period might identify as black, but also opted for biracial. Moreover, 2004 Census data shows that those between age 18 and 65 were five times as likely to describe themselves as members of more than one race than those over age 65.

Multiracial culture is all over the media — from the mixed-race cast of “Grey’s Anatomy” to MTV to the Internet, where Swirlsyndicate.com sells “interracial kids’ clothing” for “multi-culti-cuties.”

In January, a new documentary film “Chasing Daybreak,” sought to highlight what it called “America’s mixed-heritage baby boom,” chronicling the “Generation MIX National Awareness Tour,” in which five young people traveled across the United States in an RV to promote interracial harmony.

‘What are you?’

While there’s a decidedly celebratory tone to media depictions of multiracial life, the reality is somewhat different on the ground. Being identified as neither a member of one major racial group nor another — or being persistently asked the question “What are you?” — can take an emotional toll, according to Ann Van Dyke, educational director for the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission. Ms. Van Dyke travels to schools all over the state for the “Spirit” program, which seeks to address racial conflict among students.

“What we often see is the biracial students have all the problems that the other students of color have, but have a whole list of other problems as well, because they are biracial,” she said.

Elliott Lewis, author of the book “Fade: My Journeys Through Multi-Racial America,” knows first hand what those conflicts are. While the Maryland-based 39-year-old freelance television reporter passionately embraces his own chosen identity as a biracial man of black and white descent, others haven’t been so obliging.

As a light-skinned man, he has had to deal with all sorts of “What are you?” questions — and worse. In elementary school, he says other black children called him “half-breed,” while whites called him the “N-word.” Viewers have told him they adjusted the color on their television set to figure out his race. Once, he was asked by a Middle Eastern clerk in a mall if he was Egyptian. Then there was the time he was first introduced to his uncle as a child. “He took one look at me and demanded of my mother, ‘Where did you get this white boy from?’

“And then, another time, I was on assignment for a Reno, Nev., television station, and came back after a day outside in the hot sun with a tan, and one of the other black technicians looked at me and said, ‘It’s about time you started looking like one of us.’ “

For Lewis, calling himself biracial is all about freedom of choice, but there’s plenty of dissent about those choices, as there was when Tiger Woods announced on the Oprah Winfrey show that he was “Cablanasian” — a mix of Caucasian, black and Asian heritage. Many blacks were outraged, and even Colin Powell responded, saying “in America, which I love from the bottom of my heart, when you look at me, I’m black.”

If anything, the movement toward creating a new kind of racial persona, whether “Cablanasian,” “Blasian” or “Nuyorican,” is misguided, says Dr. Larry Davis, director of the University of Pittsburgh’s Center on Race and Social Problems.

“It may be in vogue to do that, but all of these are social constructions,” Dr. Davis said, adding that “African-Americans are really exactly that: Africans in America. It is who we are, even if there are some who want to get away from the title by trying to create a new group so as not to suffer negative consequences. It’s been said that this country has biracial children but only black adults.”

“There’s another quote I like to use,” he added. ” ‘Reality will tolerate fantasy but won’t spare it.’ The vast majority of African-Americans, in terms of responses from the larger society, will be perceived in existing categories. When that white cop stops you at 11 o’clock at night, he’s not going to ask you about your ancestry.”

Lewis strongly disagrees, saying he’s heard that worst-case scenario over and over again.

“First of all, it’s not a given that a police officer will identify a biracial person as black,” he said. “And just because you’re subject to discrimination doesn’t mean you hand over veto power of your self-identity to someone else. When coming to terms with our identity, we have to make sense of the sum total of our life experiences, not just those when we’re discriminated against because of our blackness.”

Much of how multiracial people identify themselves depends on how and where they were raised, added Dr. Jones, the Penn State vice provost. “If you grew up in a single-parent household, you may only relate to that parent’s heritage. If you are connected to both families, that will change things in terms of how you perceived your identity.”

Dawn Williams, 33, is able to braid the strands of her parents’ different bloodlines together without confusion or doubt.

The Fox Chapel resident grew up in Brooklyn, the daughter of an African-American mother with Cuban ancestry and a father who was a full-blooded Native American descended from the Cherokee and Shinnecock tribes. Whenever she gets the “What are you?” question, she answers by telling them that she’s a black Hispanic.

“In the Native American culture, you are what your mother is,” says Ms. Williams.

While she fully embraces her father’s Native American heritage, she notes that living in a cultural, ethnic and racial melting pot like Brooklyn, “where everyone is everything,” it was no big deal. Some members of her family married white people, so “I’ve got relatives with blonde hair and blue eyes,” she says.

“People would look at my father and think he was Cuban, or Italian. It depended on where we were, although my father mostly identified with the black culture. He listened to black music and many of his friends were African-American.” Asked what she does when confronted with a medical or educational form asking her racial identity, she shrugs.

“I put black, but I don’t need to check off a box to let me know who I am. In my family, no one’s wondering.”